This article appeared under the title “Obsolete?” in RSA Journal 1/2015

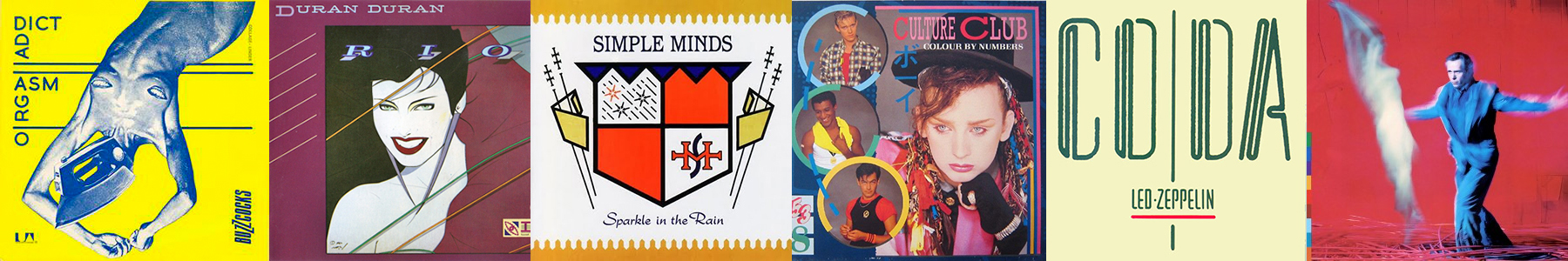

I was a designer in the music industry throughout the ’80s and ’90s, from before the introduction of CDs through to the beginnings of the digital era. I have seen the expression of a music-based youth culture evolve to become almost an end in its own right, and then find itself in a quandary as physical forms of music delivery have eroded.

I was often asked if I mourned the passing of vinyl when the CD appeared. Now I’m asked if I mourn the demise of packaging itself. My response then, as now, is that it doesn’t really matter to the designer what the packaging is, merely that its particular constraints are understood. Packaging is just one interface to the music. The application of creative energy, which once saw physical expression in record sleeves, posters and club flyers, is now realised in ‘soft’ ways. The interface is now digital, but no less compelling. The point of access is the package, and consequently, identity is expressed in ways that complement rather than define the music. It’s more important to be a Lady Gaga ‘little monster’ than to be seen carrying her album in school.

In connection with this, I began to think about the wider context of music and youth culture, and the role it plays in shaping personal identity and thus, society itself. Teenagers are growing up with the twin concerns of global ecological threat and personal economic threat. They see a life that is both exciting and, given the reach of social media, without some of the old physical limits, but this is tempered by fear of a hardto- specify, and harder to resolve, sense of foreboding. This constrains them in ways my generation had only just begun to experience.

It is within this framework that the delivery of music should be considered. Teenagers don’t have markedly different personal development concerns than 30 years ago, but they have very different vehicles by which to express them.

The swinging ’60s informed counterculture and a radical leftfield lifestyle embedded itself in society in ways that were both subtle yet all-pervasive. I count myself among a sizeable portion of the population best described as ‘50-year-old teenagers’ who see themselves as ever youthful and want to enjoy their hardwon freedoms. We are evidence of what the urban studies theorist Richard Florida termed “the rise of creativity as a fundamental economic driver and the rise of a new social class”.1

Interestingly, Florida also noted that “a vibrant music scene can be signal that a location has the underlying preconditions associated with technological innovation”. This has notably happened in London’s Shoreditch, which during the ’90s many saw as a logical overspill from Ladbroke Grove, former home of UK counterculture. And much has been written about the youthful rebellion of the ’60s, particularly on the US West Coast, having effectively given us the origins of a contemporary digital society.

In his 1989 autobiography,2 Frank Zappa proposed a subscription service to provide music on demand via cable TV, more than 10 years before iTunes and Spotify made it an internet reality. With music infinitely accessible and shareable, the need for youth to express allegiance and identify with particular sub-genres has re-emphasised the appeal of performance. Music has never been more popular, both as live event and as a personal pursuit in the home studio. The artefact has simply become the advert (or the memento) for the real experience rather than vice versa. We now live our lives on the move and in a combination of real and virtual space.

Harold Wilson’s “white heat of technology” of the ’60s promised a future with labour-saving robots taking care of daily chores. What we hadn’t expected is that our robots would be largely ‘soft’, mobile and ‘in the cloud’ (think Google and thousands of other modern-life-supporting apps). While we have been busy trying to plan the future, it has simply appeared all around us and we now hold it in our hands. Ultimately, it’s not about the vehicle, it’s about the journey we take in it.

1 Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class, Basic Books, New York, 2002.

2 Frank Zappa, The Real Frank Zappa Book, Poseidon Press, New York, 1989.