This article first appeared in On|Off published to coincide with London Fashion Week AW16, celebrating 40 years of punk.

Punk sprang up all around me in Manchester, seemingly in answer to questions I was already beginning to pose in early 1976, in the first year of a course in Graphic Design at Manchester Polytechnic. For want of personal motivation and some real purpose and direction other than simply commerce or ‘Art’ I was pre-occupied with exploring the idea of a rebirth of Dada, the anti-art movement that shook the art world early in the 20th century, as a way of channeling contrary and rebellious energies into potent artworks.

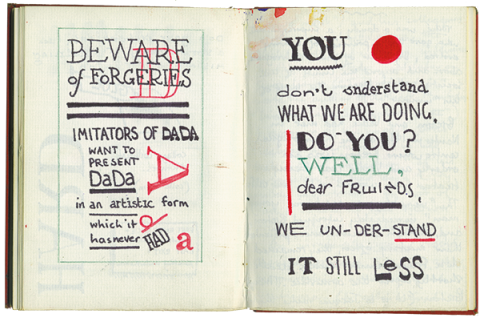

As a vehicle for experimenting with typographic wordplay, photomontage, and type as image, this inspiration from a past time had turned into a spirited, but ultimately flawed, endeavour which I engaged in for much of my spare time with other art school friends (one of whom was actually unaware of his ‘involvement’ and was justifiably annoyed when I surreptitiously and subversively included his name and image in some photo-typographic ‘manifestoes’ which I then displayed at my end-of-year exhibition).

Malcolm Garrett's sketchbook, 1976

But, in a vivid vindication of the John Lennon epithet that “Life is what happens to you whilst you’re busy making other plans”, the anti-establishment, cultural rebellion that I desperately needed was already beginning to materialise across the country in the musical underground in London and elsewhere. I just hadn’t noticed… yet.

I was relatively late in catching the start of this cultural upheaval, having missed the now legendary performances by the Sex Pistols in the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester in June of that year. (Yes, I’m one of the few Mancunians of that era who don’t claim to have been there). It was actually on a three-week visit to London in December 1976 before I finally experienced first-hand the excitement and potentency of the Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Damned and other similarly inspired and culturally motivated groups. There was a tangible spirit in the air. Seeing the word ‘S L I T S’ spray-painted in six foot high fluorescent pink letters on a wall at Marble Arch had a singularly epiphanous effect on me.

I immediately recognised that Punk was a living vehicle which could provide the creative spark I had been seeking. Here was the opportunity for me to contribute to a wholesale restructuring of music, fashion and art. In overturning everything Punk needed its own documenters and designers to create and disseminate the new world it occupied. This is where I fitted in. The world was now a living sketchpad, and everything mattered.

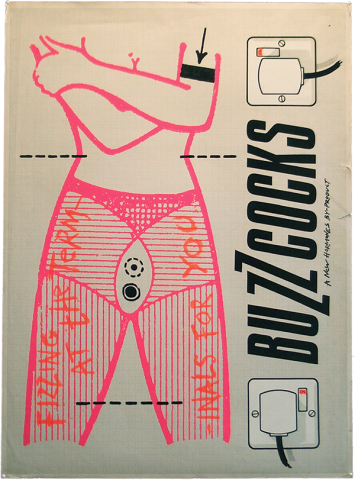

Early in 1977 I met Buzzcocks, through another college friend, Linder, and it quickly became clear that I had the motivation, passion and a particular creative intent to help them establish a fresh presence alongside the already stylised look of London Punk. Our desire was to be as different from the DIY, stencilled and paint-splashed aesthetic of the Sex Pistols or The Clash as from the rest of the music establishment. The music and lyrics were different. The sound and the look was different. Manchester itself was already proving to be different – and the rest, as they say, happened…

The first Buzzcocks poster, designed by Malcolm Garrett, 1977. Only 30 were screenprinted by hand.

It was all about attitude, energy, personal intervention and direct implementation of ideas. It was about ‘me’. It was not that I wanted to be different, per se, I just didn’t ever consider thinking in the same way as most of contemporary society, and did not share its aspirations. Now I could state that in a way that the world would notice. My work was now ‘real’ and yet was still imbued with a genuine vision of a new order. It was fuel for a new circle of friends, many of whom were soon to be in bands, both imaginary (The Blind) and real (Fireplace) and successful (Magazine). Everyone I knew became involved and active in some way, as writers, photographers, designers, as well as musicians. The audience became the players.

This precipitated a steady change throughout all media, starting with the music and fashion press and arguably ending in MTV. The intervention was absorbed. The people of the counter-culture became the cultural spokespeople, for good or bad. No longer could the spirit and energy of ‘youth’ shock the mainstream in quite the same way. If one is to look for that societal intervention today one must look online, to sites such as Wikileaks, or to the Occupy movement. A cautionary note: although we can now generate our own music, film and visual media and distribute it immediately, YouTube and Instagram are actually the new establishment. They seem radical, but they are in control of what we post.

February 2016