How a city’s commitment to design has shaped its image on the international stage

This article was first published on www.designmcr.com

On Wednesday 24 October, Tottenham Hotspur played PSV in the first leg of their Champions League tie at the Philips Stadium in Eindhoven, managing only a disappointing draw, which Spurs manager Mauricio Pochettino described as virtually ending their chances in the competition. Even as the game unfolded before an audience of 35,000, tens of thousands more were rounding off a day of exploring the wonders of design and innovation on show at this year’s Dutch Design Week, then halfway through its nine-day run in a radius of four kilometres around the stadium.

In 20 years, DDW has become Northern Europe’s largest design event, welcoming some 300,000 visitors to engage with the work of 2,600 designers in more than 100 locations, clustered in eight areas across the city.

For me – visiting just days after our own sixth design festival in Manchester culminated in the fabulous D(isrupt)M Conference at The Bridgewater Hall – the highlights at DDW included a social balconies concept linking apartments in new housing developments; an underfloor bed and storage system inspired by the eccentric Dutch farmhouse phenomenon of beds-in-cupboards; an experiment creating ceramic wallhangings with a “fabric memory”; and a range of interactive and immersive installations exploring data and memory.

‘Social balconies’ by Edwin van Capelleveen.

Woven Spaces: cloth dripped in porcelain and fired at 1260ºC, by Magdalena Wierzbicka (Piet Zwart Institute, ‘Ulterior’).

Woven Spaces: cloth dripped in porcelain and fired at 1260ºC, by Magdalena Wierzbicka (Piet Zwart Institute, ‘Ulterior’).

Those, and a fascinating exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum about the Alibaba/Jack Ma phenomenon, exploring its social, economic, technology and political dimensions, developed in partnership with the Design Academy Eindhoven.

Geo-Design: Alibaba. From Here to Your Home. DDW Exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven.

Geo-Design: Alibaba. From Here to Your Home. DDW Exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven.

For all the design products, media and installations on show, it is notable that while there are products on sale, DDW is not a fair. The crowds wandering around the festival sites and exhibitions reflect the breadth of Dutch society – young people, old people, families with children, students, and visitors from abroad. There appears no obvious bias towards either gender. School trips are much in evidence, funded I’m told by the schools themselves, which are as cash-constrained as their British counterparts but see this activity as feeding directly into the employability prospects and pathways for their students. This may be linked to the significant role of universities and art colleges in the exhibition programme, alongside major participating brands.

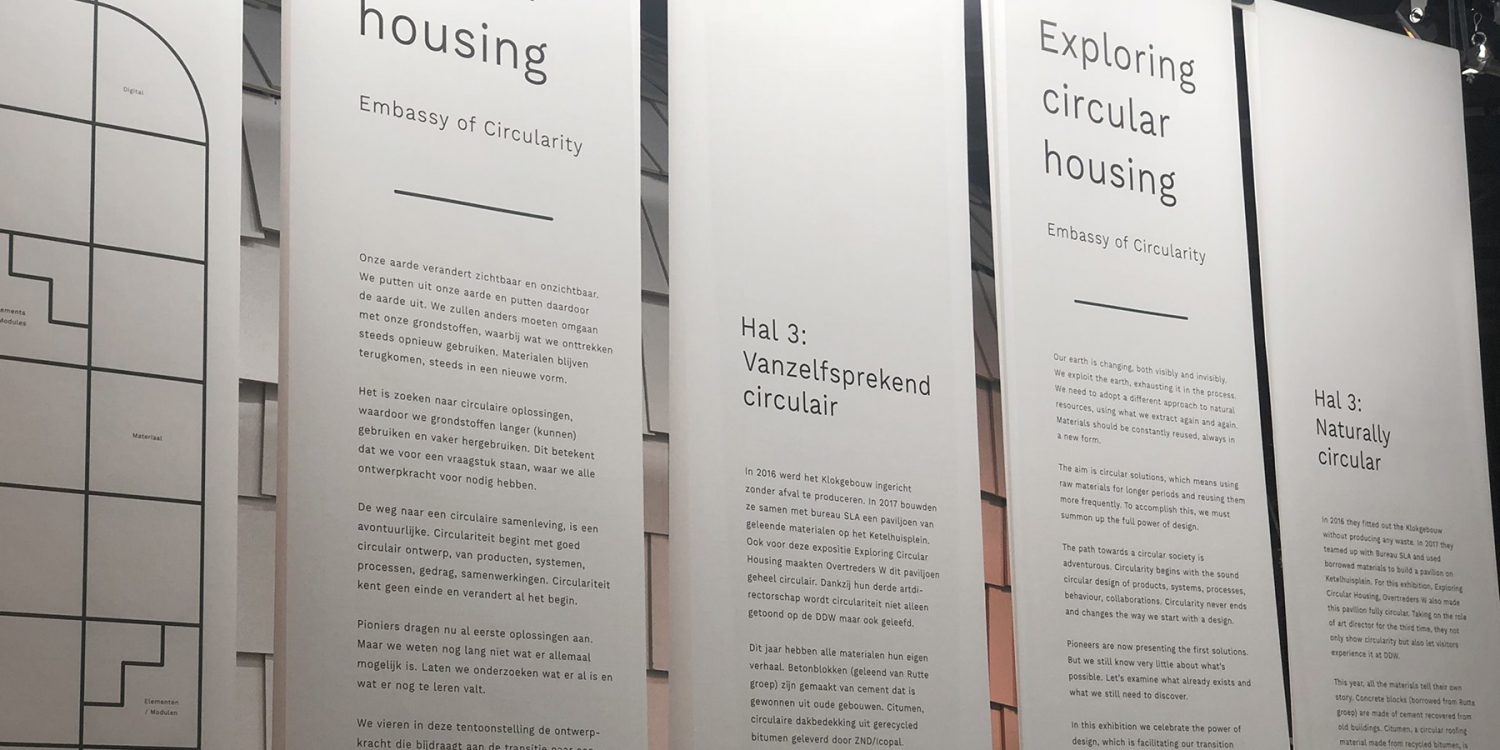

The prevailing perception is that design is offering solutions and asking questions in which we should all be engaged. This approach is reflected in programme strands (dubbed ‘embassies’) that explore design solutions for major challenge areas such as mobility, circularity, water, health, urban transformation and food.

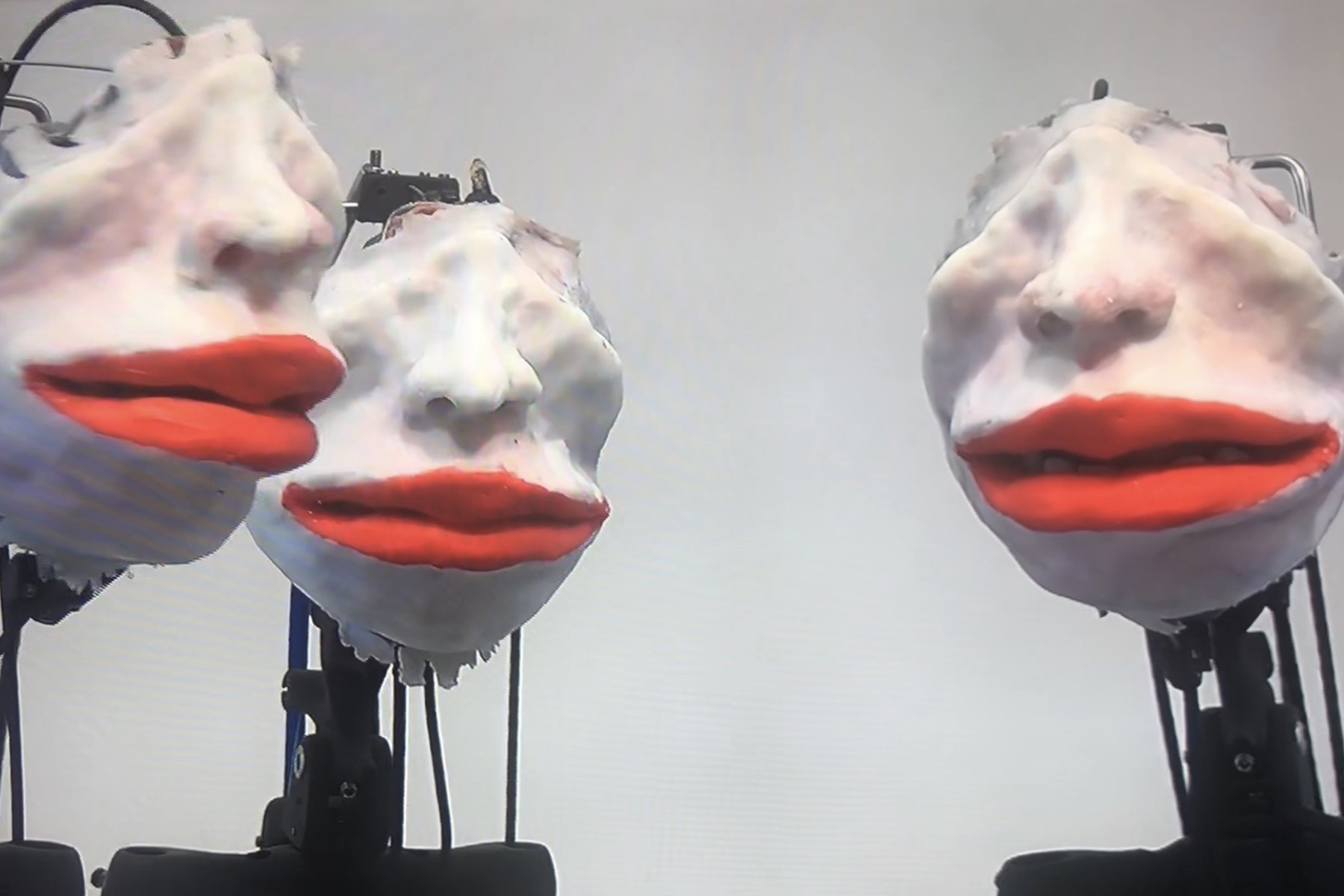

An installation in the Embassy of Circularity.

An installation in the Embassy of Circularity.

To many people in the UK, it is the football for which Eindhoven – a city half the size of Manchester in the south-east of the Netherlands – is better known. PSV, an Eredivisie football club that has nurtured Ruud van Nistelrooij, Arjen Robben, Georginio Wijnaldum and many others, started life in 1913 as Philips Sport Vereniging, the works sports club for the electronics giant Philips, inventor of cassette tapes and CDs, and supplier of gadgetry from shavers to leading edge medical scanners. Over the last half century Philips and its spin-offs have created an intensive innovation ecology in and around the city of Eindhoven, to the extent where the region attracts a third of all the research & innovation investment in the Netherlands. This is a major factor in the character of Dutch Design Week, and a reason for its remarkable success.

Stadsbrouwerij Eindhoven, a craft brewery founded in 2014, lists 48 beers in its catalogue.

Stadsbrouwerij Eindhoven, a craft brewery founded in 2014, lists 48 beers in its catalogue.

Not that DDW’s progress has been entirely without hiccups. In 2013 (the year Design Manchester was founded), the organisation narrowly avoided bankruptcy after losing nearly €1m, and was saved only by a guarantee from the municipality of Eindhoven, which today owns the festival. That investment by all accounts is paying off handsomely not only in attendances, but in the international awareness and prestige it brings to the city, its industry and its academic institutions – notably the Eindhoven Design Academy and Technical University Eindhoven. The festival and its programme are anything but parochial though. More than 20 universities organise exhibitions and events – not only Dutch institutions like ArtEZ, TU Delft and Piet Zwart Institute, but also international ones such as the Bauhaus University in Weimar, the Swedish School of Textiles and Tomas Bata University in the Czech Republic city of Zlín. DDW is a European and international meeting place for innovation and design that benefits all participants.

There are as many differences as parallels with this 20-year old phenomenon from which we at Design Manchester can learn, and we already collaborate with DDW as fellow members of World Design Weeks, the global network of design festivals in 22 cities from Bogotá to Helsinki and Beijing to Barcelona. We have our own approach, but hey, if they’re good at football, science, beer and design, there’s stuff we can do together.

Hard currency: Within the exhibition areas, this year’s programme offered close to 400 ‘short events’, including 75 workshops, 134 lectures, 22 seminars, 71 ‘experience events’, 12 parties and socials, 16 network meetings, six demonstrations and 43 gigs and music events. The basic €18 ticket offers free entry to most exhibitions and events and upgrading to the €27 ‘festival ticket’ opens the door to most of the gigs, which otherwise command entry fees of €10-€20 a piece. There’s also a €130 ‘pro’ ticket offering access to activities for professionals, including premium networking events. The festival is said to sell around 50,000 tickets with revenues from this source in excess of €1m, to be shared with event and service partners.

Main image: Koro/Choir: Mechanic Sculptures in Movement, video installation by Server Demiktas at Robot Love.