When Greta Thunberg said, “Build back better, blah, blah, blah”, she put her finger on the anger many people feel about fine words from our leaders in government and industry that aren’t matched by meaningful deeds.

But it applies to us too. What can we do that will make a difference?

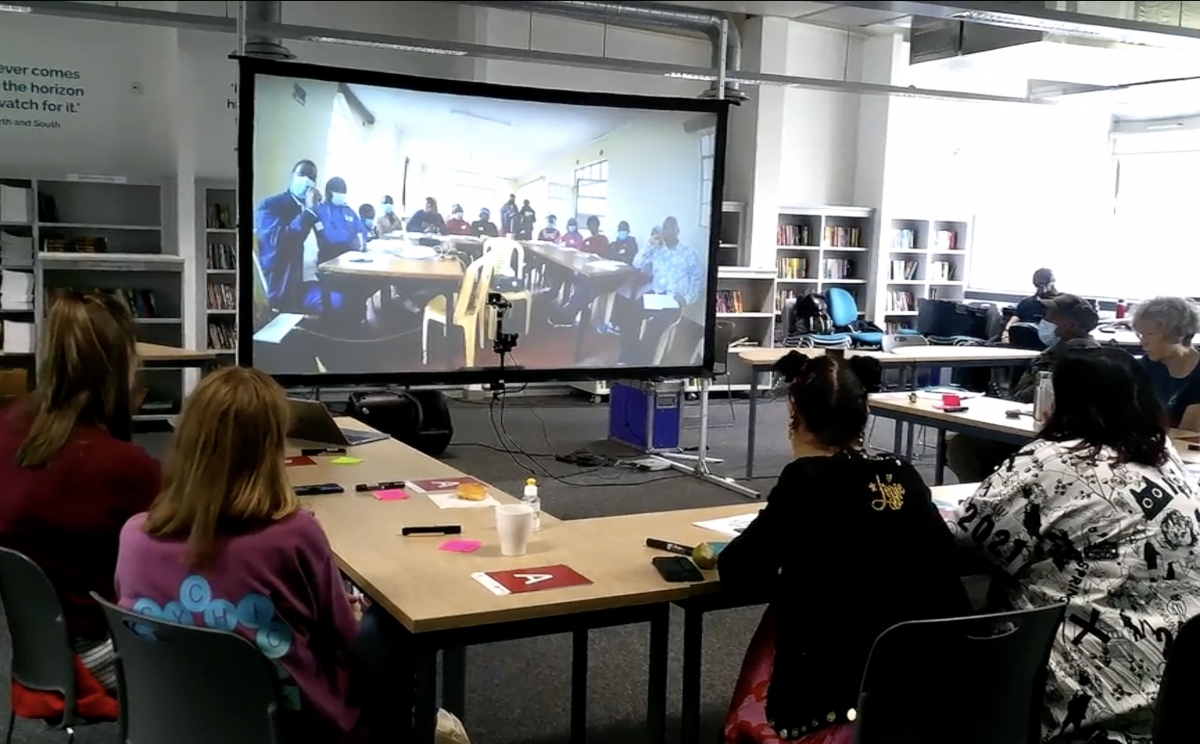

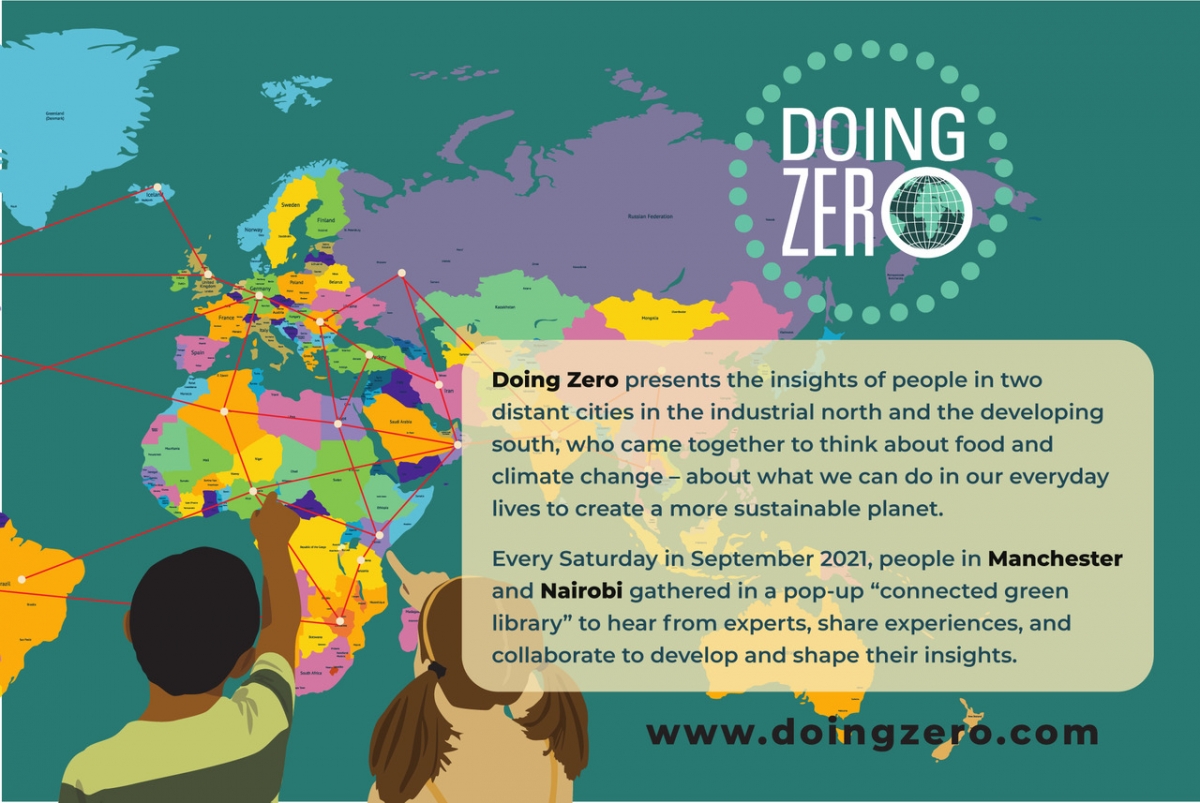

Every Saturday in September, people in Manchester and Nairobi gathered in a pop-up “connected green library” to hear from experts, share experiences, and collaborate to develop and shape their insights.

The green library was made up of two linked spaces: one in Manchester Communication Academy, a secondary school in Manchester, and the other in Dagoretti South Empowerment Centre in Nairobi, connected via a digital “fourth wall”. It was part of Doing Zero, a creative commission funded by the British Council in the run-up to COP26.

The collaboration began by listening and talking to experts.

Eating habits

Professor Sarah Bridle is an astrophysicist who has in recent years devoted herself to studying food and global warming. Humans, she explained, emit on average 6 kilograms of greenhouse gases every day, just from their eating habits. To be in line with the target of keeping global temperatures within 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, that needs to be halved. That means a big change in how we grow our food and what we eat.

A quarter of all greenhouse gases comes from food. It’s the biggest driver of global warming after fossil fuels, and it’s one where the consumer could make all the difference.

The amount of meat consumed is significantly higher in Manchester, and the food that’s eaten there comes from all over the world. In Nairobi, most of the food people eat is grown within sixty miles of where they live.

Overall, all products derived from mass breeding and farming of cattle – beef, milk, cheese, butter, yoghurt – have a serious impact on global warming because of the methane they emit. This applies to all ruminants (sheep, goats, buffalo, deer, elk, giraffes and camels too), but in the scheme of things it is our global dependence on dairy and beef that presents the greatest threat. Chicken has a much smaller impact, which could be reduced even further if they are fed more sustainable crops.

Transport, particularly by air, and packaging have impacts too, but significantly less than dairy and beef products.

Lived experience

The science does not lie, but our learning comes also from lived experience. This is the focus of the Design Kenya Society, which works with communities to solve complex African problems using design.

With Mike Muiya and Kyesubire Greigg we explored our relationship with water – with rivers and canals, the rain, and how we use water in our daily lives. We talked about how so much of our food depends on it, and how looking at the river from its origins right through its meandering journey to the sea can give us an insight into the past right through to the present day.

Can the mountain, the source of the river, also offer solutions to our problems? In African culture, before there were schools, information was passed on to the next generation through storytelling around the fire. In Doing Zero, the connected green library is our fireplace. Our future is someone else’s past. We can learn from each other and from traditional ways of life.

In Manchester, everything is available all the time, but where does it come from? Shortages are more likely to do with political problems. Overall it’s more a question of money and flying things in from all over the world when they are out of season here.

Not that imported foods always come up to expectation: Haleh’s recollection of sweet persimmon in Iran, and Adrian’s experience of fresh avocado in Nairobi, are rarely matched by their mass-produced and packaged imported cousins in UK supermarkets.

Alternatives

There are plenty of alternatives to beef, dairy and the highly processed foods many of us eat today, as we discovered from two food scientists from Reading University: Dr Simona Grasso of the School of Agriculture and Dr Martin Chadwick of the School of Chemistry, Food and Pharmacy.

Can meat ever be sustainably produced? Simona explained that the industry’s focus has been on improving efficiency and there’s also a welcome shift in popularity from red meats to poultry. Nevertheless, meat eating will still have to reduce significantly if it’s ever to become sustainable.

Alternatives include aquatic foods such as chlorella, spirulina, mussels and kelp, and terrestrial foods such as larvae, mycoproteins and cultured meat.

Insects are already commonly eaten in well over a hundred countries, though not (unless you count I’m a celebrity, get me out of here) in the richer ones. They are arthropods ¬– like shrimp, crab and lobster – and there are more than two thousand edible insect species. They’re good for the planet for various reasons: they can feed on biomass that’s unsuitable for humans which reduces the land required to cultivate them, the larvae grow super quickly, and there’s no waste as the whole insect is edible.

Undeniably though, there’s a yuk factor among older people in developed countries, and there are other obstacles to overcome before insects become a more accepted global food source.

Culture change

Some promising stepping-stones to reduce the world’s reliance on meat are in development.

A Dutch company converts “end of life organic waste” from insects into protein for use in animal feed and other food products. Another in Cambridge uses the larvae of an insect to convert organic waste into fats and proteins.

Protein-rich alternatives for vegetarians is not a new idea: Quorn is made from mycoproteins, a fermented blend of glucose, minerals and fungi. Many more alternatives are rising in popularity. A Waitrose range of hybrid meats – sausages, meatballs and burgers with one third non-meat content of fruit, vegetables and pulses – is designed to appeal to ‘meat reducers’ or ‘flexitarians’, as many people now think of themselves.

Grow it in the lab?

And then there are numerous attempts to grow the food we like in the lab, without the harmful effects, from “test tube milk”, which replicates the protein and fat combination found in cow’s milk, right through to beef, pork and chicken.

The first cultured burger, in 2013, cost a quarter of a million dollars to produce. Five years later, the cost of growing a piece of steak had dropped to $50.

Fans insist that once it looks like the real thing and tastes like the real thing at a price people can afford, cultured meat will catch on, and the first commercial, lab-grown chicken “bites” approved by regulators were served in a Singapore restaurant last December.

Crops

Martin reckons that agriculture currently produces more carbon emissions than it removes from the atmosphere, but that’s due to forest-burning, chemicals and pesticides, so although current practices are not that sustainable, the growing popularity of plant-based cuisines from north Africa and south Asia is good news for health and for the planet too.

Of 12,000 edible plant species we eat only about 200, and more than half of the plant-based foods we eat are made of just three crops: rice, wheat and maize. The reason is that we’ve focused on improving the crops we eat over thousands of years, rather than experimenting with others.

Can science help? Genetic modification and gene editing can be problematic if it’s driven by profit without regard for sustainability, but there’s no scientific reason why they can’t be used to accelerate the human-assisted “natural” selection process. This could speed up mass cultivation of newer kids on the block, like quinoa, kelp and oysternut.

Action

One of the best things we can do is make a lot of noise to let the wider public, supermarkets and big food companies know what we want. But how can we work out what that is, when we have so little information about the implications, and none is given at the point of sale?

After two weeks of discussing our shared and different experiences with the experts, we were joined by Extinction Rebellion’s Clive Russell to talk about turning insights into actions.

Clive’s view is that we cannot carry on the way we are, but most people are obsessed with production and consumption. We have to stop, think and do things differently. If we want to raise awareness, we need to be clear about what we’re campaigning about. Everyone can be involved in their own way – but it’s not DIY, it’s about doing things together.

It’s not just campaigning, of course. Doing Zero is about what we can do ourselves, and Elizabeth Onyango of Kenyan startup Ukulima Tech introduced a discussion about urban farming.

Urbanisation is advancing so fast that by 2050, more than 70% of the world’s population will be living in cities, with risks for food security, farmers’ access to markets, and degradation of natural resources.

Space for growing food can be problematic, with many people having no access to gardens. Ukulima Tech believes that vertical farming is key to promoting green cities, increasing agricultural productivity on rooftops, balconies, and in front and rear yards.

Britain has a rich heritage of allotments, but most urban farming today focuses more on extras like herbs than on bringing staple foods to the table. The ambition of Ukulima Tech’s approach inspired a range of ideas – including developing a vertical farming wall in a university café.

What were the practical insights from the Doing Zero workshops?

First, information about the impact of our eating habits on global warming is not readily available.

Second, large-scale processed beef and dairy are the biggest single factor in food-related greenhouse gas emissions and we must urgently reduce our reliance on them.

Third, access to water is at risk in many parts of the world and threatens future food security.

Fourth, urban farming and eating local, seasonal food can help support sustainable food systems in our cities.

The Doing Zero team is working with the scientists to produce climate impact information about typical diets in Nairobi, and to explore the potential of developing a labelling scheme for retail food.

They created an exhibition which was shown in the Vertical Gallery at Manchester School of Art during COP26, and they are disseminating information through film, video, social media and online resources on the project website created by the Nairobi team, and by exploring the wider potential of the connected green library.

In January they plan a follow-up collaboration to build vertical gardens in a university café in Manchester and a similar venue in Nairobi.

Doing Zero is produced jointly by Design Manchester and Nairobi Design Week. It is a Creative Commission for COP26 funded by the British Council and supported by a wide range of partners including Boot Room Communications, Dagoretti South Empowerment Centre, Design Kenya Society, Images&Co, Instruct Studio, Manchester City Council, Manchester Climate Change Agency, Manchester School of Art at Manchester Metropolitan University, SICK! Festival, Standard Practice, Ukulima Tech, University of Manchester, University of Reading and WWF UK.