Hope against fear, was how Brexiters characterised the battle. Hope in hell versus fear of the inevitable, this is starting to look like in the sober light of day. But no-one knows what happens next. Conventional wisdom is out of the window, along with the polling industry.

Does that include the wisdom that now the people have spoken, there is no way back? Is that, too, an old-fashioned idea?

But wait. If the Brexiters’ ‘hope’ is proving to be wishful thinking, there is no shortage of rosy spectacles on the other side.

It won’t happen?

First, the ‘2nd EU Referendum’ petition – which, at time of writing, has picked up more than 3.75 million signatures. Amusingly, this petition (“We the undersigned call upon HM Government to implement a rule that if the remain or leave vote is less than 60% based on a turnout less than 75% there should be another referendum”) was started back in May by the English ‘Democrat’ William Oliver Healey, who felt the present outcome, if mirrored, would not have constituted a sufficient mandate, and who is reacting with consternation to the creature he has spawned. “CAN I HAVE YOUR ATTENTION PLEASE!!!” the democratic Mr Healey shouts on Facebook, caps lock firmly on. “The petition has been hijacked by the remain campaign… my actions were premature (but) my intentions were (to make) it harder for ‘remain’ to further shackle us to the EU.” Not a sentiment that appears to be deterring those signing up to his persuasive argument.

Conventional wisdom, though, says this is a dream and Parliament will dismiss the petition out of hand. Charles Walker, Tory MP for Broxbourne and a Remainer, who as chair of the Procedure Select Committee introduced the petitions system, says that unless it attracts more than half the electorate, the petition stands no chance. But that’s not stemming the flood of signatures.

Hope springs eternal too in the breast of ‘Teebs’, a Guardian reader who has contributed occasional comments on the newspaper’s website for almost a decade. Teebs likes to think that Cameron has “effectively annulled the referendum result, and simultaneously destroyed the political careers of Boris Johnson, Michael Gove and leading Brexiters who cost him so much anguish”. He’s achieved this by handing the poisoned chalice to his successor who, Teebs reckons, will decline to invoke Article 50 because by then the consequences will be clear, and will thus be finished either way. An attractive idea, but possibly driven by desire.

Teebs was on a roll yesterday. That post at 10 in the morning was followed by a further eight responses to comments from others, and then another two posts. Thirteen hours and copious amounts of red wine later, passion had reached boiling point: “There is a disease in England and it is called Boris Johnson… Everything he does is ultimately designed to advance the interests of the entity called Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson. He will destroy not only any political party or organisation, but the EU, the UK and the livelihoods of millions of people, just to advance that entity.” It is not the preserve only of the old and disaffected to dream. Conventional wisdom however would say that Cameron’s successor will get on with the job in hand.

Anti-Iraq War march, 15 February 2003

Then there is the planned march in London on 9th July. “The power is still with the people,” proclaim the organisers. “We can change things if we are organised and passionate in our response. Let’s unite the Remain voters and those who regret their vote to leave, to turn this on its head. Lets march together with Europeans who have lived in this country and given to this country, but who were not allowed to vote for this country.” This will provide a platform for people to express their continuing anger, but conventional wisdom would rate its chances below those of the ‘We Are Many’ global marches against the Iraq war in 2003. Moreover, it could backfire if violence breaks out, which some Brexiters might see as in their interest and could easily provoke.

(Note. The 9 July march has been deleted from Facebook. It is not known if it is still planned to go ahead.)

The cry of protest by the white, anti-establishment, non-metropolitan, post middle-aged English of 2016 is just as sneering and resentful as that of an earlier generation in 1976 who felt that with no jobs and no prospects, the system was rigged against them. The prime minister, the universities, the Bank of England and the international monetary fund – they’re all liars. Malcolm McLaren might have been proud.

Immigration

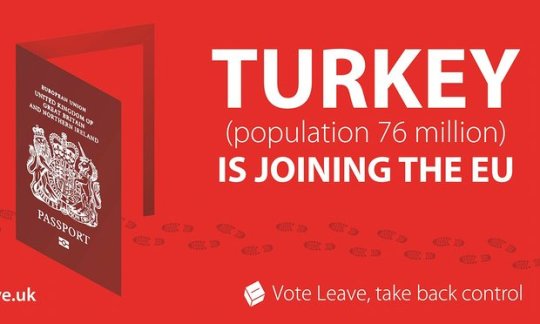

It is not surprising many feel ill-served by globalisation, which has only brought them insecurity while delivering greater riches to metropolitan elites. Brexit’s ominous success was that it managed to pin the blame for all these ills on immigrants. The reason there are no jobs is not that manufacturing industry has all but disappeared – it’s immigrants. The reason there’s a housing crisis is not that social housing has been dismantled or that prices are driven up by overseas buyers – it’s immigrants. The health service can’t cope because it has to deal with too many people. The country is full, we can’t take any more. We can’t change it while we’re in the EU, so we have to “take back control”.

But truthfully, the Westminster this control reverts to has had a far greater hand than Brussels in the UK’s shortage of jobs, housing and services that has so fuelled the resentment against immigrants. The light touch financial sector regulation that led to the credit-fuelled crash of 2008 resulted from the economic policies of Westminster and Washington governments in the thirty years leading up to that crash. The failure to hypothecate at least some of the riches brought into the Treasury by EU migrants (£20 billion in the first decade of this century) on targeted help for schools, services and job creation in areas affected by immigration is the UK government’s fault.

To be fair, the one person who directly challenged the immigrant blame narrative was Jeremy Corbyn, who pointed to the failure of successive governments to tackle issues such as wage competition from EU immigrant workers. But this had little impact and clumsily even inflamed the argument. It is only now the anti-immigration argument has won the day, that the reality may start to emerge.

More than a decade ago, I attended a lunch given by the then Chief Economist of HSBC, who expressed the view that the UK would not be able to afford the pensions and care of its rapidy ageing population unless it maintained high levels of immigration to ensure there were sufficient younger contributors in the economy. Yet the immigrant as a drain on finite resources remains the effectively unchallenged and now victorious view of the country. Like most Brexit leaders, Iain Duncan-Smith rapidly distanced himself from the promise of giving £350m a week to the NHS, but – in contrast with Boris Johnson – he was clear on immigration that the government should now deliver on the Tory manifesto commitment of “reducing net migration to the tens of thousands” by the next election, meaning 2020. He said this should start at once, but since the free movement treaty obligations will remain in force until the Article 50 deal is done, any short-term impact may be limited. The most recent figure for annual net migration into the UK is 333,000 and the underlying trend is up. So the Brexit government would plan to cut immigration by more than two thirds in the final year of the government, which itself would cause a massive economic shock.

Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond takes the view that we will soon see that immigration cannot be reduced while at the same time maintaining high growth. The trade-off between the Leave campaign’s promises of access to the European market and stopping free movement, he believes, will be the most important question determining our future. “However it is resolved,” he says, “many people will be disappointed.”

Now that he looks like the man who will have to carry the can, Boris Johnson has moved quickly to dampen expectations. The £350m weekly payments to the EU that should go to the NHS have become “substantial sums”, which “could be used on priorities such as the NHS.” The idea that people who voted Leave were mainly driven by immigration, Johnson says, is not so. “We are an open country that values immigration.” The point, it seems, was not immigration: “The number one issue was control.”

But it is hard to deny the thousands of interviews with voters up and down the country on radio and television during the campaign making it clear the control they wanted was over the border and immigration. The leaders of the Leave campaign may not succeed in fully detaching themselves from the photographic evidence of their spending promises, or to disown responsibility for the rise in hate crime that followed the vote, fanned by the campaign and empowered by the outcome. They may find it hard to quell cynicism about the sophistry of the political class. Those who voted Leave because politics was corrupt and they were being lied to may start to wonder, if we remain as open to immigration as before and if ‘control’ seems as distant and unresponsive as ever.

Boris Johnson sets out his post-referendum position in The Telegraph

On the new deal with Europe, Johnson says there will be “intense and intensifying” cooperation and partnership in the arts, the sciences, the universities and the environment. Life will go on exactly as before for EU citizens living in this country and for British citizens living in the EU. “British people,” he asserts, “will still be able to go and work in the EU; to live; to travel; to study; to buy homes and to settle down.” Significantly, he says that “there will continue to be free trade, and access to the single market.” Most of these promises are not his to deliver but in the gift of the European Union, with whom he has not started negotiating. Johnson reassuringly says that the German employers’ federation is in favour of continued free trade, but the conventional wisdom is that the price would be free movement and around £150m-£200m a week. Johnson is not alone in pushing for such an outcome. Serious Remainers including Tony Blair and Francis Maude say that the EU should now make meaningful change to the current free movement rules. If that happened, the UK could remain a member of the single market and have an arrangement on movement of labour that it “controls”.

Is that possible? Perhaps. As Maude says, “freedom of movement is coming under criticism all over Europe.” Andrew Neil put it more graphically: “Business as usual in Brussels will only fan rebel flames.” A Brexit government might view this as the best of both worlds: access to the single market while retaining ‘control’ of our laws and borders. Others may feel that paying for access to a market without influence over the rules by which we would have to abide is the worst of both worlds, but there is scope for different options to emerge during the period of negotiations.

Events, dear boy

Dave Chamberlain had come back from Brussels with a deal that’s not worth the paper it’s written on. For years, Boris Churchill had warned from the wilderness about those dictatorial Europeans (hang on, is that right?) and at last his moment had come. Fortified by the resolve of the people he stopped the European invasion and fought the bureaucrats on the beaches to protect the freedom and sovereignty of England.

– The Churchill Factor, revised edition, 2016

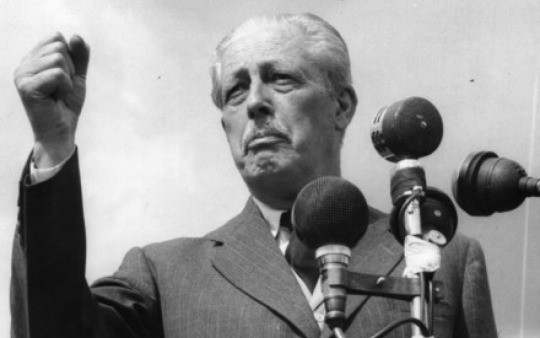

Harold Macmillan

The Harolds always knew conventional wisdom has its limitations. Wilson, during the 1964 sterling crisis, observed that “a week is a long time in politics.” Macmillan, when asked what a prime minister most feared, reputedly said “Events, dear boy, events.” The Queen appears to hold a similar view currently. After the Scottish referendum last year she issued a statement calling on the people to unite, but there’s been no word this time. Asked why, the palace drew a distinction between the decisive outcome last year and the ongoing turmoil of the present situation.

That tumult may die down, but it is clear from the movements in stocks and currencies that events in the financial markets and elsewhere could have an impact on future options. The concern is less about the current upheaval than the longer-term outlook, the Chinese Finance Minister suggesting yesterday that the repercussions will depress the world economy in five to ten years’ time. There have been some announcements about jobs in the city being moved to Paris. If this accelerates and spreads to other industries, Johnson’s legacy as London Mayor – his responsibility when he decided to throw his weight behind Brexit – may suffer damage. The tech and innovation sector relies on free movement of labour and capital for skills and investment: it too could soon be affected by the uncertainties of the lengthy interregnum.

The risks to the United Kingdom will become clearer with an unpredictable situation in Northern Ireland and the Scottish government pressing its determination to protect Scotland from a fate it did not choose. Nicola Sturgeon’s promise to withhold legislative consent may not be able to stop Brexit, but the measures the government would have to take to enforce its will could easily hasten the breakup of the union. Scotland’s avowed aim of negotiating a stay-behind deal with the EU introduces another element into the process that is unlikely to strengthen London’s hand.

Home Secretary Teresa May

Important events arise, too, from the actions of Westminster politicians. Teebs is right that the prime minister’s decision to pass the starting gun for negotiations to a successor who will not be in place for three months has changed the whole context of what happens next. There will be a contested election for the new Tory leader who will automatically become prime minister but will not have a personal mandate from the electorate, beyond the referendum result itself. Dividing lines are being drawn, with Duncan-Smith saying that the new prime minister must be someone who supported Leave, but Philip Hammond among those who say the candidate must be able to united the party and “have a credible strategy for dealing with the situation.” Johnson may the the heir presumptive but many in the Conservative party would be profoundly unhappy with that outcome and success is not guaranteed. There will be voices saying that Teresa May is a much safer pair of hands, better placed to unify the party and the country. If external events such as the 9th July march illustrate the depth of betrayal that many associate personally with Boris Johnson, his attempt to portray himself as a unity candidate and electoral asset may become less convincing even to the Conservative party membership that elects from a shortlist of two, particularly if the Labour party emerges as a credible alternative.

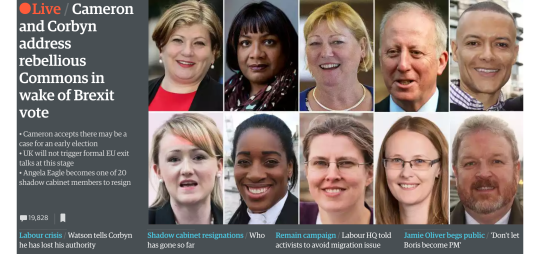

The impact of Cameron’s move has been felt in Labour as strongly as in the Conservatives, sparking Hilary Benn’s rebellion and sacking, followed by mass frontbench resignations to force a leadership election. “The reason this is happening in the Labour party,” commented Ed Balls, “is that people are very confident there will be a general election within a year.” He summed up the rebels’ expressed view: There is going to need to be a change if Labour is going to have an impact on what happens.”

Unprecedented events and “Cameron accepts there may be a case for an early election”

In the British system, Parliament is sovereign and chosen by the people in a general election. This mechanism trumps everything else, including a referendum. If Brexit is looking more calamitous in six months’ time and public opinion has markedly changed, could Labour stand on a manifesto of reversing it? If they did, it would see massive voter registration on both sides, potentially the highest turnout seen in any election outside North Korea, possibly resulting in the most decisive popular mandate. Conventional wisdom would view this idea as political suicide, but it could get Labour its highest vote ever and seems the only scenario that could overturn the referendum result if on reflection that is unpalatable to the country. Whatever its manifesto, the Labour rebels have decided they must act and some party members voting in the resulting leadership election may feel this has become more important than the fight between the Blairites and Momentum. This is not like the Scottish referendum, where the SNP could lick its wounds, score a massive victory in the next Scottish election and then bide its time to have another go. Leaving the EU cannot easily be reversed, so this is why suddenly everything is going at fast forward speed and members may be more focused on prospects at the general election than the fate of individuals.

The Brexit campaign has unleashed an ugly intolerance. Regardless of what the UK’s relationship ends up being with the EU, there will a battle for the soul of the country: nationalistic, xenophobic and intolerant or open, outward-looking and collaborative. Many who voted against Brexit will reject the idea of Johnson, having stoked the former with the same ‘control’ and ‘freedom’ refrain that is familiar from Geert Wilders’ Freedom Party in Holland, Heinz-Christian Strache’s Freedom Party in Austria and similar parties all over the continent, now claiming to be the latter. But the ugliness we see is born of resentment and alienation that runs deep because it has been ignored for too long. Thwarting their victory, even with a democratic mandate, could have even uglier consequences in the UK and across Europe.

Addressing housing, jobs and services, with priority for areas disproportionately affected by immigration, is the principal task for a government wanting to protect the values of a liberal democracy. If we’re out, we have “substantial funds” to do it with. If we’re in, Europe will doubtless want to chip in.