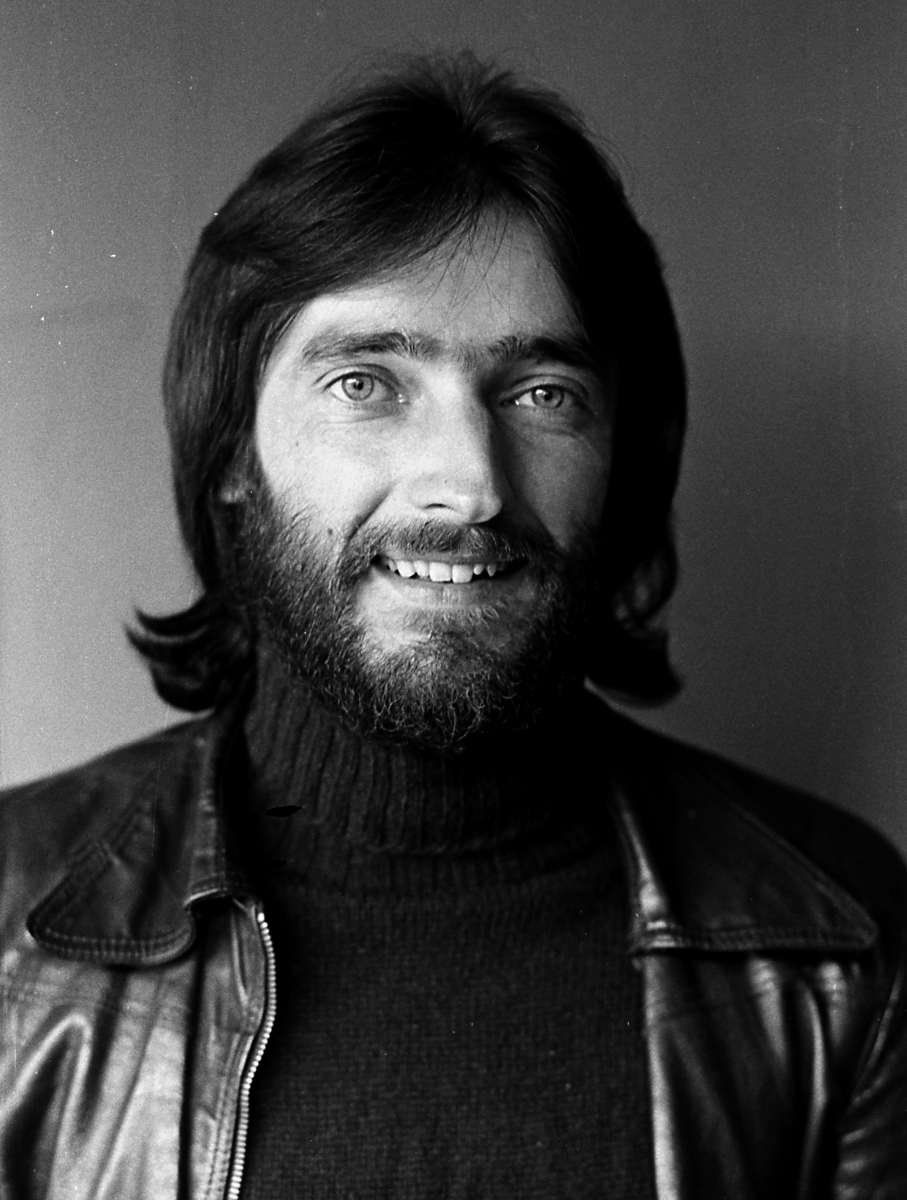

A memoir occasioned by the death of Mike Jackson on 16 December 2021. All pictures © Jake Bernard.

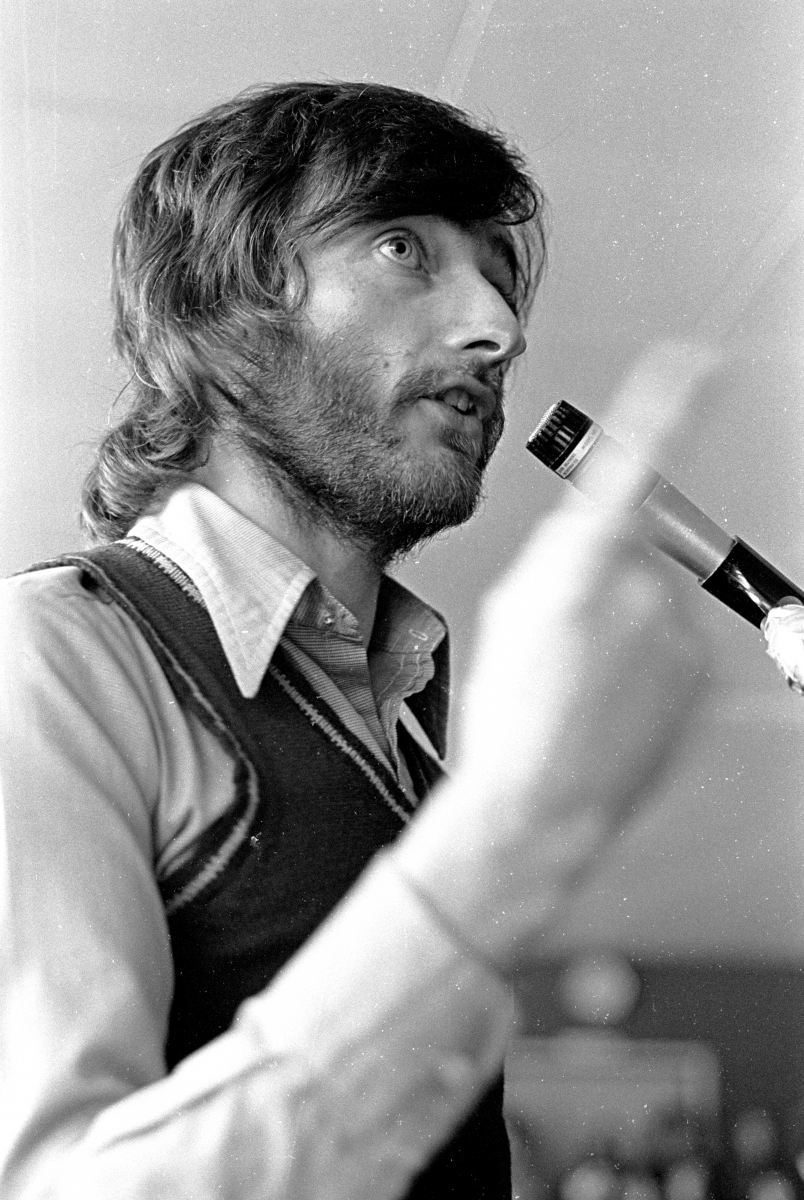

Mike Jackson, 1975

In 2007 the Labour government and trade unions, having negotiated the biggest collective agreement in Western Europe – a job-evaluated pay and grading structure for 1.1 million NHS staff – established the Social Partnership Forum to nudge the bosses-versus-workforce model in the health service ever closer towards working in partnership. This tripartite body, which brings together employers, government and trade unions, proved so useful that it was retained by subsequent administrations, and it has played a crucial role in protecting the NHS through the turbulence of the last decade.

The prime mover of this initiative, Mike Jackson, then the lead trade union negotiator in the NHS, died on 16 December aged 73 after a long battle with cancer, at his home in Watford, where he was a former leader of the Council, twice Parliamentary candidate, and for 23 years chair of the local Labour Party. It symbolised his contribution as a lifelong Labour activist, trade unionist and politician: moral clarity combined with a collaborative approach that crossed party lines in the interests of the people and causes he represented.

Warwick University

I first met Mike Jackson at Warwick University in 1974 and 46 years later, just two weeks into the first Covid lockdown, we came together to discuss what happened there and since.

The Sixties, Mike’s teenage years, were a time of opportunity for many, but the 1963 Robbins principle (that “university places should be available to everybody who qualifies for them by ability and attainment”) initially passed him by as he left school with one A-level and went straight into a succession of jobs. Nine years later, by now a factory worker at Rolls-Royce, he was accepted at age 26 as a mature student of politics and sociology at Warwick University.

Despite universal grants, working-class students were still very much in the minority at British universities and Mike was conscious that his background was different. “Because I’d been in paid employment for nine years, I didn’t have the same outlook most students would have had coming straight from school aged 18,” he said, “but I had friends who were students, and what attracted me was the fact that higher education opened doors that were going to be closed in terms of my career. The chance to get a degree – which I didn’t have when I left school – was a great opportunity.”

Founded in 1965, Warwick was an attractive university with thought-leading academics such as feminist author Germaine Greer, mathematician Chris Zeeman, magnetic levitation pioneer R.G. Rhodes and the historian E.P. Thompson, author of The Making of the English Working Class. It was one of few institutions at the time that went out of its way to encourage older, working-class students, adjusting the entry requirements to enable them to access higher education.

Here Mike met many lifelong friends and colleagues: sociology lecturers Bob Fryer and Paul Corrigan, the former going on to play a guiding role in the creation of the trade union Unison, where Mike made his career; the latter becoming health adviser to Tony Blair at No. 10 Downing Street and a key contact when Mike led the union negotiators in the NHS; the poet and data scientist Godfrey Rust, with whom I had co-founded Warwick’s student newspaper The Boar the previous year; Nita Bowes, later Clarke and now the Viscountess Stansgate, who became an official at the COHSE health union and later trade union adviser at No. 10; Andrew Dismore, who as a Labour MP was to be instrumental in the establishment of Holocaust Memorial Day 25 years later; the criminologist John Benyon; comic book publisher Nick Landau; lobby journalist David Wilby; the anti-nuclear campaigner Linda Pentz Gunter; and the KGB-spy-in-Berlin-turned-housing-spokesman for Nelson Mandela’s government Stephen Laufer among them.

Student activism

Like all of us, Mike had been radicalised by youth activism in the late 1960s – the Paris student riots in 1968, anti-Apartheid, Black Power and the Vietnam War – but he only acted on it after joining the Labour Party in 1972, when he became deeply involved in the miners’ strike that led to the three-day week and the general election in February 1974.

The student body he joined in September that year was similarly politicised. From the start, Warwick University’s close collaboration with manufacturing and industry had sat uneasily alongside its commitment to liberal traditions. Four years earlier, during a sit-in demanding union autonomy and a union building on campus, students discovered files showing that Vice-Chancellor Jack Butterworth and motor industry boss Gilbert Hunt had colluded in surveillance of the political activities of a visiting academic. The episode and its impact were immortalised by E.P. Thompson, who neatly characterised the struggle between academic liberalism and industry-demand-led education in his 1971 book Warwick University Ltd:

‘Is it inevitable that the university will be reduced to the function of providing, with increasing authoritarian efficiency, pre-packed intellectual commodities which meet the requirements of management? Or can we by our efforts transform it into a centre of free discussion and action, tolerating and even encouraging “subversive” thought and activity, for a dynamic renewal of the whole society within which it operates?’

The answer – not just for Warwick, but for universities more generally in the political context of the intervening decades – turns out to be an only slightly qualified yes, and no.

In the February 1974 election campaign, I had worked as publicity aide to Audrey Wise, Labour’s candidate in the marginal constituency of Coventry South-West, and Warwick students played a decisive role in her election as the MP by 513 votes.

In the six years since Enoch Powell’s infamous “rivers of blood” speech, the battle against racism and neo-fascism had become a key focus on campus and in factories and in June, three months before Mike arrived on campus, 20-year-old Warwick maths student Kevin Gately became the first person to die in a public demonstration for more than half a century following clashes between protesters and mounted police at a protest against the National Front in London’s Red Lion Square, which became the subject of a public enquiry by Lord Scarman. (John Benyon, students union secretary at the time, later became an authority on public order and founded the Scarman Centre at Leicester University.)

Politics and sociology was an interesting subject combination. “The sociology department was quite radical and the politics department quite right wing,” Mike recalled. “The books we read for both subjects were the same, but the interpretation that was given on them was often quite different in the two departments.”

Mike became immersed in student activism immediately on his arrival with the second general election that year in October, which Audrey Wise won with an increased majority. The following month, Nita Bowes and I won election as students union secretary and president respectively on a joint “Broad Left” ticket and in December, three months after arriving on campus, Mike was voted in as union treasurer – a key player in the momentous upheavals on campus the following spring.

Union Building

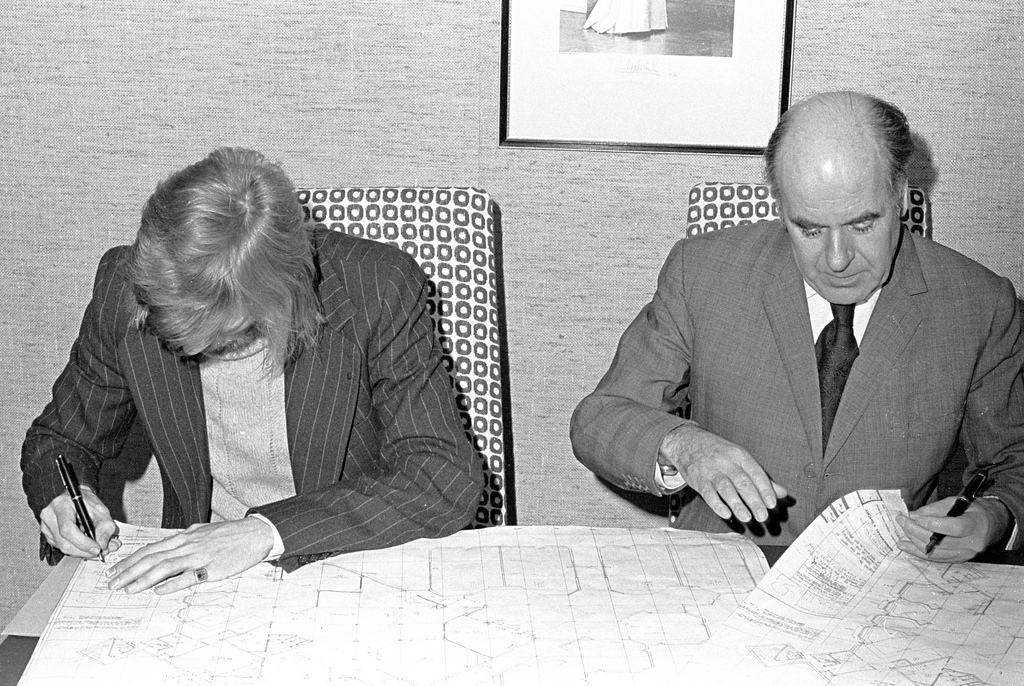

“The students union”, Jack Butterworth had said after the 1970 sit-in, “will never have its own building.” But the campaign – supported by numerous academics including Chris Zeeman – had not gone away. In February 1975 negotiations finally bore fruit for control of the soon-to-be-completed “Social & Dining Stage II” building to be handed over to the students union.

Kasper de Graaf and Vice-Chancellor Jack Butterworth sign the agreement to give students control over their own building

The occupation

A separate dispute, however, was already under way – one that ended less happily for the students, and one we can now see as pivotal in the political shift from universal to targeted benefits, from 1960s investment in free education for all, to 21st century graduate taxes and downplaying universities as “the only option”.

The UK economy was under growing pressure and student grants were not keeping pace with rising costs. Education Secretary Reg Prentice’s assertion in the House of Commons that grants were sufficient to cover “economic rents” did not square with the university’s 33% increase in rent for student accommodation on campus and in January the students union had begun a rent strike which culminated, on 21 April, in a mass meeting resolving to “effect an immediate, orderly and disciplined occupation of the Senate House and the telephone exchange”, thus bringing the university’s regular administration to a halt.

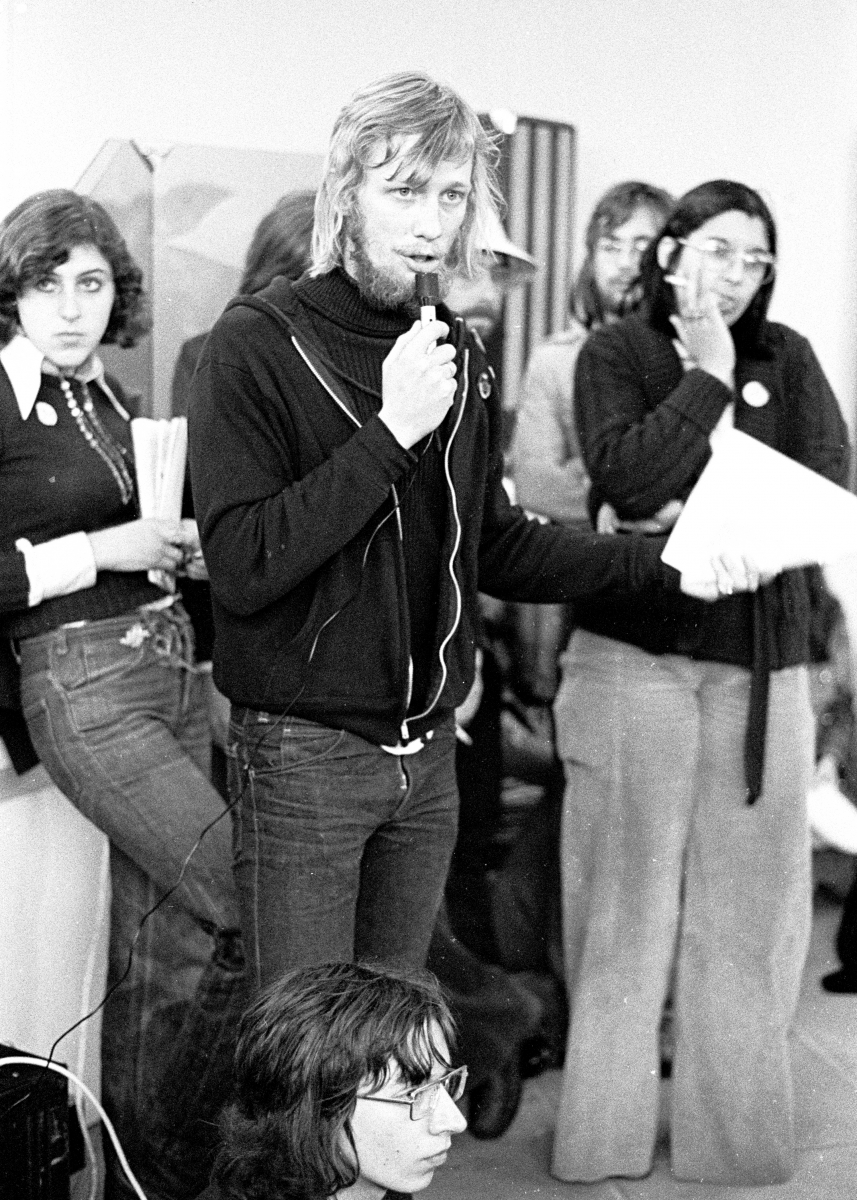

Kasper proposes the motion to occupy, flanked by (from left) Linda Pentz, Stephen Laufer, Andrew Dismore and Nita Bowes

The vote to begin the occupation

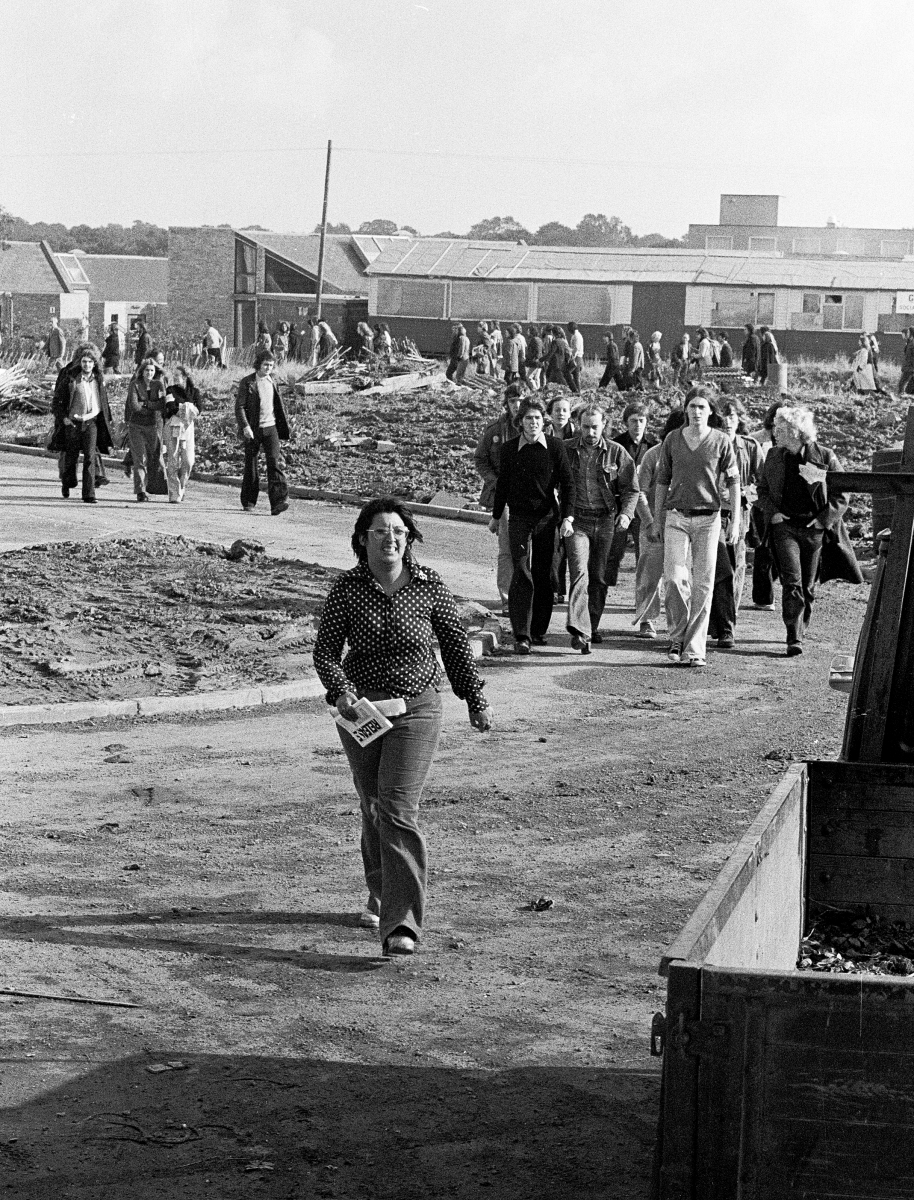

Nita Bowes leads students through the building site that was then Warwick University to Senate House to start the occupation

A similar dispute two years earlier, when the university had sought to impose 24% rent rises, had resulted in a favourable settlement but this time Warwick students found themselves at the vanguard of a national strike with some 20 universities and colleges facing similar action. Sympathetic as some universities were, they were in a cleft stick with rising costs and cuts in government funding. The new Labour government – which the following year went cap in hand to the International Monetary Fund for a $3.9 billion loan – had no magic wand and the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals resolved to stand firm.

Mike addresses a students union meeting

So, for the next 3½ weeks, did the students. Mike: “We had nightly open meetings in the occupation discussing where we were and reporting on the organisation, the outreach work that was being done, the collection of money for the rent strike fund and issues around the care of the building as well. Keeping morale up was part of that process. We gathered a good number of activists around us. I remember sleeping on the floor in a room with you and Nita, but not every night. We had a rota, so we had nights off for a bit of rest and recreation.”

We had regular mass meetings addressed not only by local student leaders and activists, but by sympathetic as well as opposing academics and by national figures including future education and home secretary Charles Clarke, then president-elect of the National Union of Students (NUS), and national vice-presidents – now broadcasters – Alastair Stewart and Trevor Philips. All opinions were welcome.

Kasper and Charles Clarke lead a rent strike march in Coventry

Eviction

When at length the university moved to expel the students from Senate House, just four names were added to mine as alleged ringleaders in the petition to the High Court: Nita Bowes, Mike Jackson, Brian Deer, who went on to become a celebrated investigative reporter at The Sunday Times, and Andrew Dismore. The High Court, mindful of a potential unintended impact on squatters’ rights, ruled against the university for not having named all the occupants – a tricky undertaking, as the occupation enjoyed overwhelming support on campus and the personnel in Senate House changed every night. Lord Denning in the Court of Appeal, endorsing the university’s narrative that we were a tiny minority of rebels, had no such qualms and ordered our immediate eviction, which was duly actioned at daybreak on 15 May by 500 bobbies carrying riot shields that were not required as the students moved quietly and sheepishly with sleeping bags and pillows under their arms out of the Senate House and into the Arts Centre next door.

Police prepare to evict the students from Senate House

As Education Correspondent Peter Wilby wrote in The Observer the following Sunday: “The Warwick occupation was not only remarkably well-disciplined, it also enjoyed exceptionally wide support, with nearly half the university’s 3,400 students frequently attending union meetings to endorse its continuation, despite the term’s grants not being paid and threats that the final exams and degree results would be delayed.”

A typical mass meeting outside Senate House

Mike was central both to that discipline and to the widespread student support. As treasurer he’d established a bank account for students to safeguard the rent they were withholding and a separate strike fund to support students in financial difficulty. As, so often, the adult in the room, he argued for unity and common sense. Following the Denning judgment we had several meetings with the superintendent at Canley Police Station and we knew the order would be enforced with what we thought would be about a coachload of police.

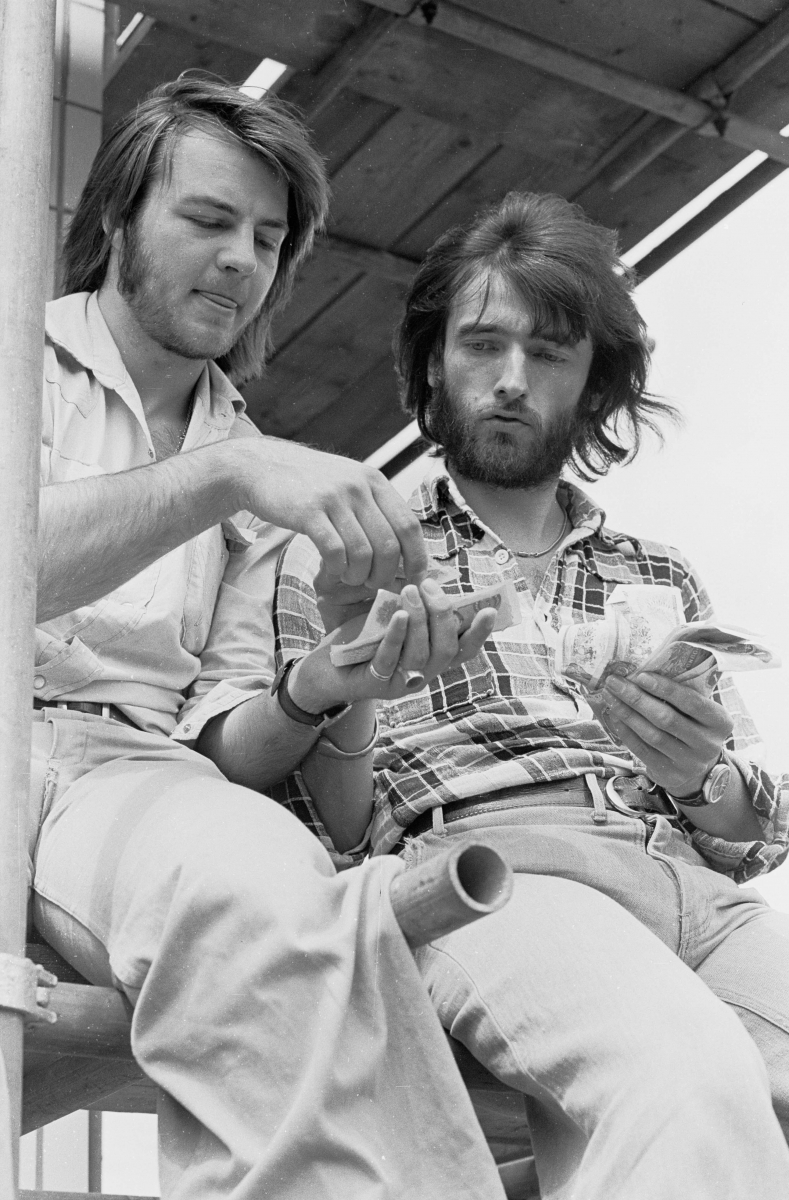

Phil Dixon (left) and Mike counting contributions to the Rent Strike Fund

“That night there was a meeting in the occupation about what we should do,” Mike recollected. He found himself arguing with former student president Pete Ashby, then still some years away from becoming a responsible and influential figure in the TUC and New Labour. “Pete wanted us to have a sit-in and be pulled out. I argued very strongly that in the context of the small rooms and the narrow corridors of Senate House, that was a potential risk to students who were going to get hurt.” Common sense prevailed and the choreographed denouement attracted praise even from the university’s spokesman.

No future?

Meaningful defence of the idea that universal student grants should be sufficient for anyone, from any background, to get a university degree without recourse to other sources of income was at an end. This coincided with the erosion of tenure for many occupations including university lecturers, and a rapid rise in youth unemployment. The Sixties optimism where everything seemed possible had given way to uncertainty and diminishing prospects for the young. For me, the 1975 student revolts bled seamlessly into the anguished cry of punk that rocked Britain’s art colleges the following year. Malcolm McLaren, Jamie Reid, Johnny Rotten. No future, pretty vacant. Don’t expect. Do it yourself.

Back at Warwick we turned our minds to making a success of the union building, which provided a sustainable foundation for the union’s support to members in the decades that followed, with turnover rising to around £8m a year and an £11.5m renovation in 2008-09.

Clause 4

Nationally we resolved to assert our voice as mainstream Labour, to distinguish ourselves both from our Communist and “non-aligned” partners in the Broad Left coalition that dominated the NUS, and also from the sectarian Revolutionary Socialist League which was masquerading as the Militant Tendency inside the Labour Party and for some years had had the upper hand in the Labour Party Young Socialists and in the National Organisation of Labour Students (NOLS). A group of us formed Clause 4 – so named to burnish our left-wing credentials as adherents of Clause 4 of the Labour Party Constitution, written by Sidney and Beatrice Webb in 1917, which committed the party to “(securing) for the workers by hand and by brain the full fruits of their industry” through common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange. I became the first convenor of Clause 4 and a group of us – including Mike Gapes, a former students union secretary at Cambridge who in 1975 moved to Middlesex Poly to spend more time with his politics, and Dave Toke, today an authority on energy politics at the University of Aberdeen – began to formulate our distinctive position in a series of articles and pamphlets.

The Labour Government in 1976-77 was dominated by Premier James Callaghan and Chancellor Denis Healey. Energy Secretary Tony Benn was still supporting nuclear power and some years from challenging Healey for the deputy leadership of the party in 1981 – the high watermark of the hard left’s bid for Labour supremacy.

The Militant Tendency was formally proscribed under Labour leader Michael Foot in 1982, and roundly condemned following its disastrous mismanagement of the City of Liverpool by Foot’s successor Neil Kinnock three years later – but Labour did not fully shake off Militant until 1991 when its two MPs, Terry Fields and Warwick contemporary Dave Nellist, were finally ditched as Labour candidates for the next election. But the tide had started turning against Militant in 1976, with Mike Jackson playing a leading role.

In April 1976 I had withdrawn from the university and from active politics on the sudden death of my father in Holland to earn a living as a journalist, as I was about to become a father myself and had no visible means of support.

Now led by Mike Gapes – and with John Carr, a key figure in Peter Mandelson’s instant rebuttal operation that helped Labour win its landslide victory in 1997, as national organiser – Clause 4 gained strength in the student movement. The Militant grip on NOLS was broken when Gapes was elected as the organisation’s chair for 1976-77. Note 1

Mike Jackson at this time was working closely with his Warwick flatmate Phil Dixon to promote the Clause 4 Labour ascendancy and he was elected to succeed Mike Gapes as chair of NOLS in 1977-78, with Dixon taking on the role of Clause 4 organiser from John Carr.

Labour’s financial support for the NOLS chair job had been withdrawn when the organisation was under Militant control, so to support himself, Mike enrolled on a postgraduate Cert Ed course at the Roehampton Institute, which attracted a mandatory grant. The following spring, Labour put up its first independent electoral slate for NUS executive in a loosened alliance with the Broad Left, and Phil Dixon was one of those duly elected.

NUPE and Watford

When the time came to move on from student politics, Mike applied successfully for a job as area officer for the National Union of Public Employees, organising and training a dozen branches in the London region and negotiating with the NHS and London boroughs. It was a job he enjoyed, but it was to be more than a decade before his union career really took off. During the 1980s, Mike was more driven by politics in Watford. In the 1979 election he worked as an aide to the Labour candidate, Tony Banks, who was then still on the Greater London Council and through him reconnected with Nita Clarke, then press secretary for GLC Leader Ken Livingstone. “Nita was in political transition,” he recalled. She had been a Communist at Warwick, but “it all changed after that. She became much more mainstream and eventually quite a strong Blairite.”

Mike was elected to Watford Borough Council in 1980, becoming deputy leader in 1988 and leader in 1990. He stood for Parliament as the Labour candidate for Watford in 1987 and 1992. “I really neglected my trade union career at that time,” Mike told me. “I did the job, but I had no aspirations to do anything more.” The focus was the 1992 general election, in which Labour was expected to do well. “We had great hopes, but we still lost. This was just at the time my marriage [to his first wife, Judi Jackson] was breaking up as well, so I made a conscious decision to step back from politics and threw myself into the trade union job.”

Mike never abandoned Watford, remaining Labour Party chair for 23 years until January 2020, when he stood down for health reasons. But the shift towards his trade union career proved opportune. The next year, informed by the work of Bob Fryer, NUPE combined with NALGO (the National and Local Government Officers Association) and COHSE (the Confederation of Health Service Employees) to span the public sector as Britain’s largest trade union Unison. Mike was promoted twice and as a national officer in 2004 he supported the chief NHS negotiator, Paul Marks, in negotiating the biggest collective agreement in Western Europe, called Agenda for Change. When that agreement was concluded, Marks stood down for health reasons and Mike became the new chief negotiator, responsible for implementing the agreement and laying the ground for the next step: replacing what was called the Staff Council with the Social Partnership Forum two years later.

The NHS

Mike’s dealings with government were formally through weekly meetings with Health Department senior officials and monthly meetings with the secretary of state – Alan Johnson until 2009 – with whom he co-chaired the Social Partnership Forum. But when it came to important decisions the officials would always say, “we’ve got to get this past Downing Street first.”

“No. 10 had a team which shadowed ministers and secretaries of state, so somebody in Downing Street is the prime minister’s person on health matters.” That person was Mike’s old Warwick tutor Paul Corrigan, and although they had little or no formal contact – “the Downing Street people were invisible, but they had a big influence over what would fly and what wouldn’t fly during that period” – there was in effect an important collaboration between student and tutor when it came to decisions about the health service. Note 2

In 2009, Andy Burnham was appointed to take Alan Johnson’s place.

“Andy was a really good guy,” said Mike. “The big thing was that some people in the government were pushing for greater involvement of the private sector in the provision of healthcare. They introduced competitive tendering – not just for traditional things like portering and catering, but for direct provision of healthcare.”

That was, as Mike put it, “a big no-no”, but it was a difficult balancing act.

“On the one hand we wanted to oppose the drift to the private sector, but on the other hand we had to negotiate deals to protect members transferring to the private sector and social enterprise organisations that were being set up to run NHS services.”

Andy Burnham was more sympathetic and together they figured out what to do. “He and I were the architects of what we called the NHS Preferred Provider. We got it written into all the documents and manuals on how you commission services, that the default provider was always the NHS. So you had to demonstrate that the private sector or social enterprise was a better option, not just on price but a whole range of other criteria as well.”

This provision did not survive the transition to the Coalition Government in 2010, “but it was an effective policy,” said Mike.

“As trade unions we had to show that we were opposed to the privatisation of certain services, but on the other hand we had to do the best we could for those services and for the members who worked in them. I think we got the balance right.” Note 3

Mike retired from Unison in 2011.

The Warwick story

How relevant was the Warwick story to what happened later? “It’s an important story in the development of Warwick University,” said Mike, “and a wider picture of the politics of the UK and young people during that period. I think it’s a relevant story to tell.

“I always remember [politics lecturer, later professor] Zig Layton-Henry saying to me in my last months at Warwick, ‘you could have done so much better than a 2:2 if you hadn’t been so involved in politics, but I still think that, in the long term, what you’ve done here will be of value.’ I think that’s true. If you look at many of us, it wasn’t about what academic achievements we made at Warwick, it was the whole experience. And that has been lost a bit, don’t you think?”

A dozen or so of this group of activists still meet once or twice a year, including the photographer and TV editor Jake Bernard, whose pictures for The Boar have created such a compelling time capsule of the period, and actively discuss politics and world affairs on the “Old Boars” WhatsApp group – with Mike a leading voice and moral arbiter until very recently.

Stephen Laufer and Mike Jackson, August 2017

Mike was always clear in his views, but – his determined opposition to entryists with their own programme and platform notwithstanding – never sectarian. In February 2020 he was presented with an “Outstanding Contribution to the Labour Party” award and a pot of allotment jam by then Labour Leader Jeremy Corbyn, who commented that “I can’t think of Watford without thinking of Mike Jackson.”

Few in Labour, new and old, would disagree that he truly was the heart and soul of the Party.

Mike Jackson is survived by his wife, the barrister Sue Sleeman, daughter Alice Nicholson and three grandchildren.

Notes

1 The Conservatives were also starting to make some headway for the first time in more than a decade, with Anna Soubry – her destiny as Mike Gapes’ Change UK bedfellow still unimaginable – elected to the NUS Executive in 1979.

2 Nita Clarke was also at 10 Downing Street as Tony Blair’s trade union aide, but since Mike’s focus was solely on health matters and Nita’s on government-union relations, they had no significant contact at this time. When Gordon Brown took over at No. 10, Nita became director of IPA (the Involvement and Participation Association), where she still is today, promoting social partnerships across the economy – including the ongoing Social Partnership Forum in the NHS.

3 Andy Burnham commented: “I was so touched to read what [Mike] said about me and I can honestly say that the feelings he described were entirely mutual. I truly loved the way he went about things. So principled and yet so practical. You catch that perfectly and it is why Mike always stood out to me. What I wasn’t aware of were all the other amazing things he did and that just makes me admire him even more.”