Playing chamber music in an art gallery is hardly unprecedented, but you know to expect something unusual when the musicians are Manchester Camerata and the gallery is the Whitworth.

Henry Lamb and Mandy Burvill

Each committed to the highest standards in presenting traditional art forms, neither is afraid to try out new things.

The occasion, on 17 November, was a concert featuring the rising piano star Alexander Ullman in the West Gallery.

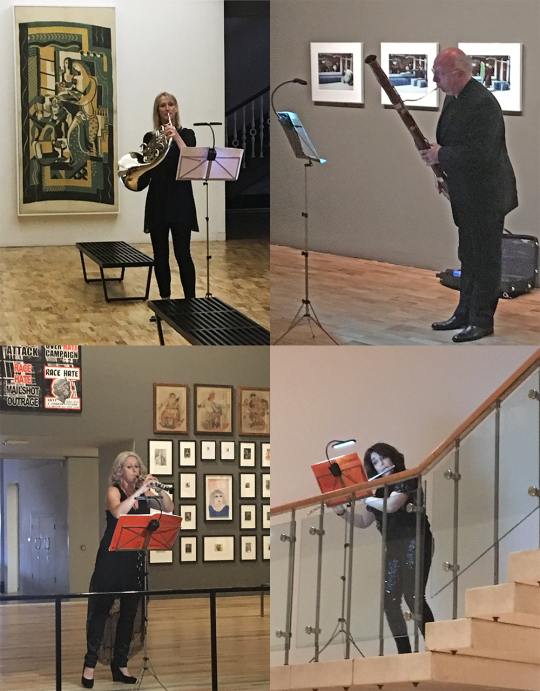

The chosen innovation, unnerving at first, was quickly captivating. The gathering guests were slightly awkward as they eyed one another – still holding coats and bags, the West Gallery cordoned off – when suddenly Naomi Atherton’s horn illuminated the textiles gallery with the eerie beauty of Gallay’s ‘Grands Caprices’. This began a buskers’ tour, where the audience was drawn from gallery to gallery with a series of serenades.

It was in the ‘Visions of the Front’ exhibition that the connection between sound, space and spectator was most poignant, with Mandy Burvill striking up Stravinsky’s 1919 Pieces for Clarinet standing next to Henry Lamb’s ‘Advanced Dressing Station on the Duma 1916’, in a place that had opened to the public just a few years before the Great War. This was not just music in a gallery: it was this music in this room, this audience transported by these musicians to a range of historical and cultural destinations.

In New Arrivals, it was twentieth century compositions for bassoon (Chagrin’s ‘Souvenir Lointain’ and Ridout’s ‘Caliban and Ariel’) performed by Laurence Perkins. Then it was right back to the 1730s – overlooked by the gallery’s founder Sir Joseph Whitworth and former director Margaret Pilkington in the Portraits gallery – to hear Rachael Clegg perform a Telemann Fantasia on oboe; and we stayed in the early 18th century for Marais’ ‘Folies d’Espagne’, written for viola de gamba, performed on Amina Cunningham’s flute.

Clockwise from top left: Naomi Atherton, Laurence Perkins, Amina Cunningham and Rachael Clegg.

All this was but the prequel to a more conventional setting for the main event, these musicians all coming together with the 25-year old London-born pianist Alexander Ullman – still studying at the Royal College of Music, winner in 2011 of the First Prize at the Liszt Competition in Budapest, described as gifted by no less a figure than Vladimir Ashkenazy – to perform a programme ranging from duets to sextets. This was kicked off by a solo rendition of Debussy’s ‘Syrinx’: Pan’s flute played, as is customary, offstage – in this case from an open upper gallery, by Cunningham.

The ensemble then came together for Roussel’s Divertissement Op. 6 for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon and piano, a great Debussy-influenced piece that shows the wind instruments to great advantage.

The entire programme was 20th century but for Mozart’s Quintet for Piano and Winds in three movements – a work he completed in 1784 at the age of 28 and described in a letter to his father as the best thing he’d ever written. Ullman showed in this performance and the next – Poulenc’s grief-stricken elegy to the horn player Dennis Brain, who died in a 1957 car crash – that he can deliver the music with skill and emotional depth.

We returned to Stravinsky for ‘The Infernal Dance’, one of the highlights (or ominous and fateful lowlight, more accurately) in ‘Firebird’, the ballet he wrote for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes which launched his career.

Alexander Ullman and principal musicians of Manchester Camerata perform Poulenc’s Sextet

This was by any standards a most enjoyable concert, the more so because of the connection established between musicians and audience. If you can take performance excellence as read, then interpretation, passion and interaction between the players offer richness and depth of experience. That was nowhere more evident than in the final piece, Poulenc’s tuneful sextet, where from the giant musical sneeze that opens it to the final bar, the fun of playing was infectious.

Manchester is a city of creativity and radical thinking, where success depends on talent and commitment to excellence, balancing unique individual contributions with harmonious team effort. In that regard it makes little difference whether the music Manchester Camerata play was written today or 300 years ago: there’s a lot that the emerging young entrepreneurs, pioneers and venture capitalists of Manchester’s creative tech scene can learn from this great group of musicians.